A movie-studio maven, deep in the West Coast style.

John Graas: Jazz Studio 3 (Decca, 1955) (recorded January 1955)

French horn player and composer John Graas, another Kenton stalwart, was the headliner on volumes 2 and 3 of the 6-volume Jazz Studio series, a somewhat obscure but important document of the more cerebral side of West Coast jazz. Previn plays on three tracks, alongside such figures as Charlie Mariano, Zoot Sims, and Jimmy Giuffre. Graas’s thoroughly refracted version of James P. Johnson’s “Charleston” gets a bit lost in the weeds, but the two jazz movements from Graas’s third-stream Symphony no. 1 are more interesting: a moody swing “Sonata Allegro” (to which Previn contributed some tasteful comping and a brief, restrained solo) and a whip-fast “Scherzo,” in which, after some angular obbligatos that owe more than a little to Shostakovich’s first Piano Concerto, Previn uncorks a crisp, torrential improvised cadenza.

Despite Previn misremembering almost all the personnel (the rhythm section was actually Curtis Counce, Larry Bunker, and Howard Roberts), I’m reasonably sure this was the session that yielded this anecdote, which Gene Lees printed in the September 1991 issue of his Jazzletter:

Years ago, when he was still working as a studio pianist in Los Angeles, Andre was on a record date with a rhythm section that included Ray Brown, Shelly Manne and Barney Kessel. The rest of the orchestra was of like caliber. The music was more or less experimental avant-garde jazz by a composer whose work, Andre said, he didn’t care for.

One of the tunes was to be played at a ferociously fast tempo, with a change on every beat. When it came to the solo section, one musician after another tried it only to crash in flames.

Finally the solo was assigned to Zoot Sims, who sailed through it effortlessly.

At the end of it, Conte Candoli said: “How did you do that, man?”

Zoot said, “You guys are crazy. I just played I Got Rhythm.”

Milt Bernhart Brass Ensemble: Modern Brass (RCA Victor, 1955) (recorded March 1955)

Previn wrote an arrangement and an original for this album. Bernhart—a studio and big-band veteran who made a career out of brief bursts of reliable brilliance (that sublime, hair-raising trombone solo on the Frank Sinatra-Nelson Riddle version of “I’ve Got You Under My Skin”? Bernhart), brought together a clutch of West Coast brass for this session: himself, Shorty Rogers and Ray Linn on trumpet, John Graas’s French horn, Maynard Ferguson on euphonium (!), Ray Siegel on tuba. Previn proves much more interested in the low, mellow part of that line-up than any high-wire fireworks. His version of the Gershwins’ “Looking for a Boy” might be a little too much warm milk, a brief burst of vinegary clusters notwithstanding; but Previn’s own “Hillside” is a lovely stretch of mellow harmony.

Pete Jolly: Jolly Jumps In (RCA Victor, 1955)

Another arrangement, this time for a fellow prodigy. Pete Jolly was a pianist, a composer, an arranger, a studio stalwart, and a longtime fixture in West Coast jazz clubs with his trio, but, before that, he was the “Boy Wonder Accordionist,” a skill he displayed alongside the piano on this, his debut album. It’s the squeezebox that’s featured on Previn’s scoring of Jerome Kern’s “Why Do I Love You?,” in a sextet with Rogers, Giuffre, Counce, Roberts, and Manne. The clean cool-jazz treatment almost plays like a pocket version of Leonard Bernstein’s Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs.

Georgie Auld: I’ve Got You Under My Skin (Coral, 1955) (recorded December 1954, February, April 1955)

A touch of jazz might peek in at the margins of this one, but Previn’s orchestrations for this collection by swing saxophonist Auld are mostly pure mood music, string-heavy and leisurely. Still, Previn seems to be having a bit of fun—his version of “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” with Previn providing some smooth, glassy cocktail riffs behind the slinky voices of Jud Conlon’s Rhythmaires, is a droll take on late-night, last-call mist.

Ella Fitzgerald: Sweet and Hot (Decca, 1955) (recorded April 1955)

Previn arranged and conducted four of the tracks on this collection of Decca singles, and, as with his charts for Auld, his contributions fall very much on the “Sweet” side of the ledger. But it’s pretty skillful stuff—pure MGM velour, but giving the star enough room to play around with melody and rhythm. “I Can’t Get Started” is the most piquant, with a poker-faced oboe counter-melody repeatedly getting pushed aside by brief, roguish hints of swing.

Let’s Get Away From It All (Decca, 1955) (recorded April 1955)

Previn ventures into concept-album territory with a round-the-world collection of songs: “Moonlight in Vermont,” “Flying Down to Rio,” “Serenade to Sweden,” and so on. Fredrickson and Cottler are back on guitar and drums, with Red Mitchell—another future Previn familiar—stepping in on bass. (Cottler would later play on Frank Sinatra’s very similarly-themed album Come Fly with Me! One wonders if the Chairman directly appropriated the idea.)

It’s all suave and stylish, though you can hear Previn seasoning the mix with bebop and West Coast post-bop spice. “Sidewalks of Cuba” is in the latter vein, bits of arranged counterpoint surrounding unflappable cool.

“On a Slow Boat to China” has somewhat more thump and edge. The track might be even more arranged than “Sidewalks of Cuba,” but sounds more loose. A few bars into the melody, Previn already is restless.

Throughout this album, one can start to hear exactly what it was that Previn initially took from bebop. It’s not really harmonic—his improvisations remain largely melodic and chordal, even when he extends those chords out a bit (see below). It’s not really rhythmic, either; Previn’s rhythm is still devoted to a flowing, swinging line, but without, say, Dizzy Gillespie’s Latin clave foundation, or Charlie Parker’s holistic, surreal concept of time, in which any fractional subdivision might be a plausible launchpad or landing spot for an improvised flight. Rather, Previn borrows a more elusive quality: touch. It’s bebop’s sound and articulation that Previn assimilates into his playing. (Some two or three careers from now, when Previn composes concert music and inserts some jazz into the proceedings, his most common indication to the players will not be in jazz tempo or in jazz rhythm or any sort of dotted-rhythm approximation, but with jazz phrasing, which tells you something about how he thinks in jazz.) To over-generalize and over-simplify: Previn is still playing lines in which one can hear echoes of Cole’s playing, or even Tatum’s, but Previn is breaking up (and roughing up) those lines with bop-like accents. Is that a form of bop? It’s close. In a blindfold test in the May 1958 issue of Metronome, Nat Cole himself, hearing Lennie Tristano’s “Blue Boy,” mistook it for Previn. (Cole was not all that enthusiastic, saying that Previn was “a greater musician than a jazz musician”.)

At the same time, Previn is embracing the post-Kenton possibility of modernist piquancy. There’s a little detail in “Slow Boat to China” that’s emblematic of Previn’s own-terms assimilation of the West Coast and bebop styles: the brief break in between the statement of the tune and Previn’s improvised choruses.

This is almost but not quite a twelve-tone aggregate. One can imagine another West Coast pianist going the extra mile and coming up with a truly dodecaphonic riff, or lifting something from Nicolas Slonimsky’s Thesaurus of Musical Scales and Patterns, or the like. A bebop player might end up with such a chromatic collection by way of stretching a dominant-seventh chord or replacing chords in a progression with substitutes transposed a tritone away. But Previn is neither schematically expanding the pitch field or structurally reworking the harmonic scaffolding. Instead, he’s taking the sound produced by such maneuvers and reframing it as an almost classical-style ornament, melodically shifting up and down by steps and half-steps, rather than harmonically shifting up and down by, say, tritones—the B-major triad in the middle of that riff is functioning less as a tritone-away replacement for F than a shimmering half-step embellishment of the C-major-triad collection that immediately precedes it. Chromatic-neighbor moves like this, in various guises, will show up often in Previn’s jazz playing and arranging. One can almost think of it as Previn’s way of reconciling the vocabularies of bebop and its progeny with the essentially decorative approach to jazz harmony and elaboration that he learned from Tatum and Cole.

Lyle Murphy: 12-Tone Compositions & Arrangements by Lyle Murphy (Contemporary, 1955; re-released in 1957 as Gone with the Woodwinds!) (recorded August, October 1955)

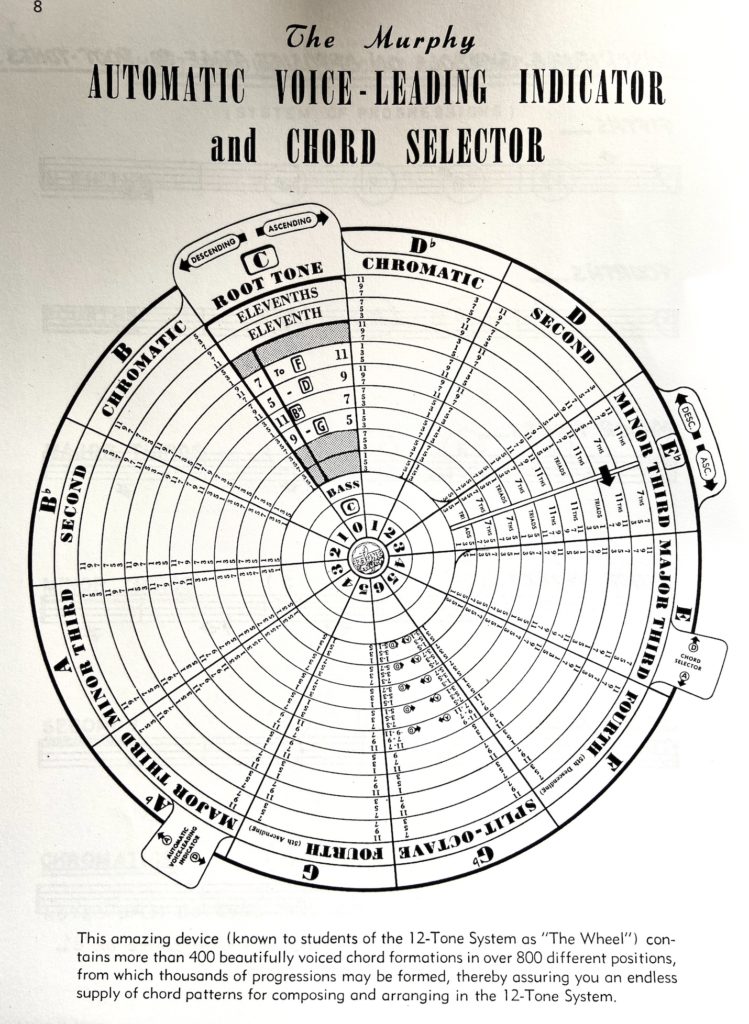

I think this is a key document of the musical milieu in 1950s California, not so much for its content (fascinating as it is), but, rather, for the number of threads—of style, of practice, of personnel—that it gathers together. In the first place, it is emblematic of the vogue for systematic composition that touched both the jazz and film-composing worlds at the time. First there was Joseph Schillinger’s System of Musical Composition; then there was Arnold Schoenberg, who took up residence in Los Angeles in the 1930s, where his students included film-music types including Oscar Levant and David Raskin; and then there were further innovations, like Schoenberg pupil George Tremblay’s Definitive Cycle of the Twelve-Tone Row or George Russell’s influential Lydian Chromatic Concept.

Lyle “Spud” Murphy, a reed player who pivoted into writing big-band charts (most notably for Benny Goodman) and then worked as a studio and film-music arranger, was one of the most interesting of these figures, and one who made the biggest splash in the West Coast jazz scene. He was a generation older than most of the practitioners and, thanks to his theoretical and pedagogical bent, became a kind of guru to a number of jazz and film composers in the LA movie-and-records ecosystem. After finishing a four-volume treatise on Modern Arranging, Murphy published Creating New Sounds in Music with a 12-Tone System in 1949 (a precursor to the “Equal Interval System” that would become Murphy’s magnum opus).

The numbers on the album are all written or arranged according to the system (with one of the originals, the 5/4 “Triton,” actually appearing in Murphy’s book as an example). It all seems fairly punctilious, but the players—Buddy Collette, Russ Cheever, Jack Dumont, Chuck Gentry, and Abe Most on winds, with a rhythm section of Previn, Manne, and bassist Curtis Counce—find the grooves, making a stronger-than-usual case for this sort of rarified jazz. Previn, in particular, is on point throughout.

Previn would never adopt any strict compositional system, steering clear of dodecaphony (though he did admit, many years later, to cribbing a row from George Tremblay.) He was too curious and eclectic at heart, and plenty prolific by his own devices. But the sort of high-concept approach to arranging epitomized and crystallized here was already informing Previn’s approach to jazz, in a more casual but still crucial way.

This, it should be noted, was Previn’s first recording for Lester Koenig’s Contemporary Records, the quintessential West Coast jazz label in the 1950s and early 60s. Previn would soon become one of the label’s marquee artists.

Mel Tormé: It’s a Blue World (Bethlehem, 1955) (recorded August 1955)

A host of arrangers worked on this collection from the Velvet Fog: Marty Paich, Russ Garcia, Al Pellegrini (who also conducted). Previn’s sole contribution, a glossy mid-tempo version of the Gershwins’ “How Long Has This Been Going On?,” walks up to the door of a swinging beat without ever ringing the bell, but the way it keeps the rhythm simple and broad, giving Tormé room to gently dance around the melody, anticipates strategies Previn will utilize on the easy-listening records he’ll make in the 1960s.

Betty Bennett: Nobody Else But Me (Atlantic, 1955) (recorded September, October 1955)

Rogers and Previn divided up the arrangements for this album, with Previn taking the ballads, but still lending piano to Rogers’ more swinging, uptempo assignments. The two took joint credit on the Gershwins’ “Treat Me Rough.” (One wonders who was responsible for that number’s brief, bubbly scat-singing-and-horns chorus, one of the less predictable things on the record.) Previn’s arrangements are straight out of the MGM playbook: lush, lilting, and making surprisingly resourceful use of his chosen instrumentation: two flutes, oboe, clarinet, bass clarinet, French horn, piano, harp, and bass. He takes the occasional solo in Rogers’ charts, with his turn on “You Took Advantage of Me” showing unmistakeable signs of a new referent: Oscar Peterson.

(Also, compare Previn’s light-footed, Bacardi-silver “Sidewalks of Cuba” on Let’s Get Away From It All with Rogers’ decidedly heavier, Bacardi-gold version here.)

The liner notes, by critic and Bennett fan Ralph J. Gleason, offer a taste of the sort of critical jazz border patrol that will stalk Previn for years to come.

This album is no jazz album any more than Paul Whiteman’s band was a jazz band for the presence of Bix and Tram and the others. But it has its jazz moments and all of them are not due to the singer herself, true jazz girl though she is. Included among the men on the date are a number of top flight jazz musicians—who are also top flight studio musicians, ready to cut anybody’s charts at a moment’s notice…. Despite the presence of these men, it is not a jazz album.

This was the last time Previn would appear on record with Rogers. But Shelly Manne, who played drums on Rogers’ arrangements, would soon become Previn’s favorite partner.