Eyeing the exit.

Sound Stage! (Columbia, 1964) (recorded April 1963)

For their follow-up to André Previn in Hollywood, Previn and John Williams exchanged the orchestra for a big band and silk for steel. Their goal seems to have been to make an album where everything is as punchy as possible; even the supposed contrasts—an easy-swinging “When You Wish upon a Star,” a ballad-tempo “Stella by Starlight”—reach brawny, brassy catharsis. There’s inherent danger in every track showing such swashbuckling muscle, but somehow this album never palls, partially because the repertoire and style frequently are at fruitful odds, and partially because Previn, whether from inspiration, bravado, or restlessness (or, maybe, all three), is in an especially brash mood.

Previn’s improvised solos are fewer and shorter than usual, just enough to remind you that it’s a jazz album, but they’re sharp and pithy. In a big-band context, Williams’ arranging style has a prowling, sinewy quality, and the hits hit hard. It’s by far the jazziest of the three albums that Previn and Williams made together. In a way, it’s an unrepeatable exercise—another collection in this hell-for-leather style could only have brought diminishing returns—but it’s a sensational album.

Soft and Swinging: The Music of Jimmy McHugh (Columbia, 1964) (recorded October 1963)

The title is the conceit: half an album of orchestral arrangements, Previn, Mitchell, and Capp slipping in and out of lush string passages like a nightclub group going off and on break, and half an album of just the trio. The “soft” tracks can get fairly swinging, though, and a lot of the “swinging” tracks are definitely on the soft side. And there’s a few places where all the moods and modes jostle for position in a surreal way. Take Previn’s arrangement of “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love.” There’s some polyrhythmic parallel figures in the strings (not unlike Williams’ arrangement of “The Last Time I Saw Paris” on André Previn in Hollywood), a flurry of 12/8 blues licks from Previn, a thumping-swing go at the first phrase of the tune from the trio, a wash of strings under the second phrase, a typically wild Previn reharmonization of the turnaround back into the repeat of the first phrase, eight bars of hard-bop soloing, half a phrase from the orchestra in swelling, harp-glissando MGM mode, then the final half-phrase from the trio, with Previn rolling out Red-Garland-type block chords. And then there’s a deceptive cadence, bumping the whole track up a step. And then the orchestra comes in with even more swooning. And so forth. The track finishes with an especially elliptical set of harmonies, followed by a tremolo string chord Previn might have lifted from Bernard Herrmann’s pocket. It’s positively dizzy.

As for the second side, it’s almost as if Previn wanted to sneak a “proper” jazz album onto the racks without anybody noticing. On “Lose Me Now” and “When My Sugar Walks Down the Street” (the latter with Previn doing his best Basie impression) the trio sounds like they’re trying to outdo the strings for mood, keeping everything at a plush simmer. But then there’s a pointed take on “Diga Diga Doo,” and a slightly rowdy triple-time prance through “It’s a Most Unusual Day,” and a jittery, deconstructive take on “Exactly Like You.”

André Previn and His Quartet: My Fair Lady (Columbia, 1964) (recorded April 1964)

My Fair Lady was something of a talisman for Previn. It had prompted his most successful jazz recording. That led to his scoring Gigi, which won him his first Academy Award—and had generated another jazz album, as did Lerner and Loewe’s Camelot. When Warner Brothers finally made their film version of My Fair Lady, Previn once again got the call, and won his fourth and final Academy Award. (He gave the longest of his acceptance speeches: 51 words.) The film must have seemed a good opportunity for another jazz interpretation of the score. And not just to Previn—Manne teamed up with singers Irene Kral and Jack Sheldon and a John Williams-arranged big band for his own 1964 My Fair Lady album, with the “un-original cast,” as the cover promised. (Manne’s album is a grand time: Williams’ arrangements are wildly intrepid, and hearing Henry Higgins’ fussy disquisitions in Sheldon’s lackadaisical drawl is priceless.)

Still, revisiting past triumphs is a risky business, and both Previn and Manne’s remakes failed to come close to displacing their earlier effort, in the marketplace or in the culture. How could they? The Previn-Vinnegar-Manne My Fair Lady was a phenomenon. As playwright (and future Previn collaborator) Tom Stoppard recalled, “Everyone had [the 1956] My Fair Lady album, just as everyone had Sinatra’s Songs for Swinging Lovers.” The recording had so defined jazz versions of the score that, in 1960, the classically-trained Trinidadian ragtime star Winifred Atwell actually recorded a note-for-note transcription of Previn, et al.’s version of “Get Me to the Church on Time.”

That might be why Previn’s 1964 My Fair Lady is so adamantly different. It’s a quartet, not a trio, Mitchell and Capp joined by Herb Ellis. It pits five songs that were included on the earlier album against five that weren’t. And Previn’s settings are especially mercurial. He’ll sometimes jump from stylistic pastiche to straight jazz on a phrase-by phrase basis: “Without You” alternates a minor-mode funeral march with mid-tempo swing, “I’m an Ordinary Man” an ominous tango with breakneck bop. There’s a lot of metrical skylarking in the head arrangements: “You Did It” hitches its 2/4 melody to a 3/8 accompaniment, “On the Street Where You Live” is kettled into 5/8, and “With a Little Bit of Luck” crests each chorus with a brief shift from 4 into 3. And there’s at least hints of pushing into new territory. “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly” starts out with Previn in comfortable, Red Garland-ish style, but, by way of a bluesy Ellis solo and one of Previn’s steelier anthologies of hard-bop licks, ends up on the verge of rhythm-and-blues. “Get Me to the Church on Time” returns as a robust boogie, as close to rock-and-roll as Previn had ever got.

Still, when Previn appeared on The Andy Williams Show the following year, he brought a version of “Get Me to the Church on Time” that was a lot closer to the 1956 album than the 1964. You can’t argue with success.

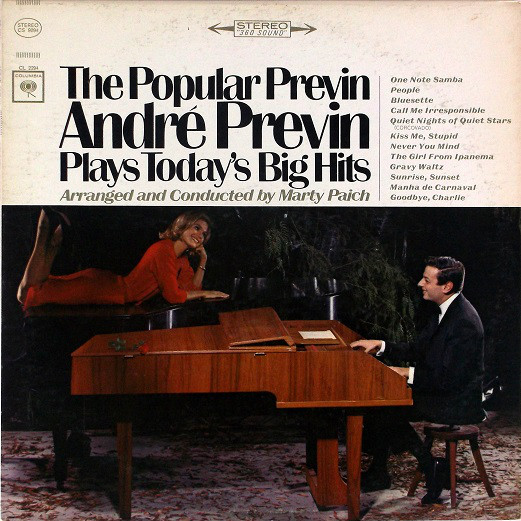

The Popular Previn: André Previn Plays Today’s Big Hits (Columbia, 1965)

Marty Paich is the arranger on this album, which starts off strange and gets stranger in a very 1960s way. It’s not the first time Previn has played a harpsichord on a recording, but it’s the first time he’s played it enough to get the instrument on the cover.

(I’m pretty sure the harpsichord in that photo is a Sabathil, which is itself pretty redolent of the 60s.) Previn’s improvising, so dependent on touch and articulation, loses a lot when he tries it on the harpsichord, and, except for a flight on “One Note Samba,” he turns back to the piano for his solos. But even those are pretty limited, tightly slotted into the general atmosphere, which slides between string-heavy bachelor-pad smooth, trying-a-little-too-hard sassiness, and anything-goes grab-bag notions. By the time an aggressively bubbly female chorus barges in on the Previns’ “Kiss Me, Stupid,” it feels both surprising and not.

Buried in this album is the makings of another, possibly more interesting one, a Previn-plays-bossa-nova collection. There’s three Jobim compositions here, plus the Bonfá-Maria “Manhã de Carnaval,” and listening to Previn try and fit his style to those songs’ inimitable nonchalance is one of the record’s more interesting side plots. It’s not so successful a marriage, but given, at this point, how infrequently Previn took his jazz out of a few comfort zones, there’s a certain fascination in listening to him attempt the connection.

(Previn’s occasional interest in the harpsichord reached its peak around this time. The year before, he had made trenchant use of it in his appropriately lurid score to Paul Heinreid’s immoderate Bette-Davis-plays-twins horror film Dead Ringer.)

André Previn Plays Music of the Young Hollywood Composers (RCA Victor, 1965)

In his liner notes to this album, his first upon returning to RCA Victor, Previn apologizes to the “dozens” of colleagues whose music did not fit the stated requirements of this album: the music had to be recent, and it couldn’t be “too symphonic in concept to fit into this particular niche.” That Previn is thinking about his easy-listening albums as a niche product is a change, I think, from his earlier piano-and-orchestra albums, which seemed to be more devoted to making the most idiomatic use of the given instrumentation than trying to fit it into a market category. That said, the arrangements, shared between Previn and John Williams, and Previn’s ear for quality material elevate this one above the average. One gets the feeling that Previn, with one foot out the door of the movie business, really wanted to make this album as both a parting gift to his friends and, maybe, as a justification to their bosses.

The treatment of some of the more familiar music is less than apposite: the liberties taken with Henry Mancini’s then-new Pink Panther theme are interesting but unnecessary, and Elmer Bernstein’s guileless music from To Kill a Mockingbird does not translate well into the sophisticated ambiance at all. But there’s some real gems. Johnny Mandel’s music from The Americanization of Emily gets some crystalline Previn piano and a suave Dick Nash trombone solo. Previn’s slinky solo in and around Michel Legrand’s “I Will Wait for You” (from The Umbrellas of Cherbourg) is a fair distance from his jazz playing, but still effective. No fewer than four Previn originals turn up, though, to be fair, “A Happy Song” was cut from Robert Mulligan’s underbelly-of-Hollywood melodrama Inside Daisy Clover, and that film’s “You’re Gonna Hear From Me” (given a reading of equable luxury) would go on to be probably the Previns’ most-recorded song. Williams gets to resurrect “Tuesday’s Theme” from Bachelor Flat’s cutting-room floor, and his “A Million Bucks” (from the TV show Checkmate) is the album’s jazziest highlight.

This was Williams and Previn’s last pop collaboration, though they would continue to work together, most notably tag-teaming the music for the 1967 film version of Valley of the Dolls, Williams providing the score, the Previns providing songs. (And Dory Previn would continue to provide lyrics for some of Williams’ songwriting efforts.) Outside of film, Previn conducted the Houston Symphony in the premieres, in 1965 and 1968, of Williams’ “Essay for Strings” as well as his often-revised but never-recorded Symphony no. 1. (They would also be united by the ruthless vagaries of the film business: the Previns’ songs for the 1969 musical version of Goodbye Mr. Chips were rejected by the studio and replaced with a score by Williams and lyricist Leslie Bricusse.)

The Fortune Cookie (dir. Billy Wilder; United Artists, 1966) (recorded June, July 1966)

This was Previn’s last all-original film score (though he would do arrangements for a handful more). Billy Wilder’s comedy, like so many of his films, swings from sweet to breathtakingly cynical, so Previn gets to run the gamut, too. Part of the brief is some aggressive oomph for the antagonists: “The Bad Guys,” as it’s called on the soundtrack album, is one of Previn’s slinkiest jazz charts, all dry-powder, big-band swank and sneer, with Gerry Mulligan making stylish work of the strangely Prokofiev-like melody.

A redo of Two For the Seesaw’s “Second Chance” translates its swoon into a wash of fleecy saxophones (playing in the background of a barroom brawl). There’s also a rendition of Cole Porter’s “What Is This Thing Called Love?” sung by actress Judi West. In the film, it’s played, and explained, as a record of an audition for a jazz group. Previn’s arrangement is an intricate and lithe stretch of West Coast cool. As in All in a Night’s Work and Two For the Seesaw, Previn seizes on the excuse for a bit of diegetic, in-story jazz, and lavishes more attention and skill on it than it needs—a sign, maybe, of where his enthusiasm lay.

Previn with Voices (RCA Victor, 1966)

Previn wrote the liner notes for this album, too. They’re breezy and pleasant, as usual, but, read between the lines, and he’s starting to sound a little passive-aggressive.

It is always fun to sit in the offices of Joe Reisman, the RCA Victor record producer, and discuss various ideas for forthcoming albums…. We went through just such a session prior to the making of this album. I think I recall that the suggestions for the day included “Great Songs from Horrible Shows,” and “The André Previn Trio Swings the Shirley Temple Song Book,” and for weird reasons no one was enthusiastic….I had made enough arrangements for piano and string orchestra to fill my librarian with dread at the prospect of filing away even one more, and suddenly the idea of a piano album accompanied by just voices took shape.

The choral arrangements (augmented by string bass, the lightest of drums, and a harp) were by Wayne Robinson, a veteran who had worked alongside David Rose at NBC; Robinson and Reisman also teamed up on some television assignments in the 60s. In general, the slower the music gets on this album, the better; the choir is, partially by necessity and partially by arrangement, very rhythmically square, but when there’s room for Previn navigate inside the beat, you can hear the possible virtues of the whole piano-and-choir idea.

Two selections deserve particular mention. A chaste, mock-classical version of “Michelle” marks the only time Previn ever essayed a Beatles song. And this is also the first appearance of “It’s Good to Have You Near Again,” one of the Previns’ most beguiling songs. The version here is a little bland. Luckily, another singer would soon record it.

Leontyne Price and André Previn: Right as the Rain (RCA Victor, 1967) (recorded March-April 1967)

Reviewing this record for High Fidelity, Morgan Ames erroneously attributed “It’s Good to Have You Near Again” to Rodgers and Hart. Previn couldn’t have been more pleased to send the correction: “What a marvelous case of mistaken identity!”

For much of the title track, Price seems to signal an Eileen Farrell-ish approach, low in her range, a little stentorian, a little too rich for the context. But then she starts singing like, well, Leontyne Price, yards and yards of organza unspooling from the bolt, and this album turns sublime. The songs are familiar Previn favorites—he’s done “Nobody’s Heart,” “A Sleepin’ Bee,” and “They Didn’t Believe Me” several times before. (There’s even a momentary modulation-reharmonization in “Love Walked In” that’s almost identical to the version on André Previn Plays Gershwin from back in 1955.) It all sounds fresh, though. Previn’s imagination is in high gear. The orchestral selections include an intriguingly Britten-esque accompaniment for “It Never Entered My Mind” and a pointedly (Richard) Straussian take on “Falling In Love Again” that feels like nothing so much as a couple of exceptionally bright students pulling faces behind the teacher’s back. The jazz numbers, with Previn in a trio with Ray Brown and Shelly Manne, are more straightforward, but full of exquisite moments.

Previn’s ability to mediate between the pop and jazz genres and a classical vocal sound will feature prominently in his later jazz revival.

All Alone (RCA Victor, 1967)

As Previn was quoted in Leonard Feather’s liner notes: “The idea came about by a process of elimination.” In more ways than one. All Alone closed out Previn’s first quarter-century career as an active jazz musician. It also was recorded against a backdrop of thoroughgoing change. Previn had slowed his film work to a trickle. His attention was almost fully occupied by classical music: in 1967, he became music director of the Houston Symphony, and he was about to become principal conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra. At the same time, his marriage to Dory Previn, the deepest personal and professional relationship of his life thus far, was cracking under the strains of his absences and wandering eye and her mental difficulties. (They would separate the following year.) The former factors may account for Previn’s return to the solo-piano format, which he found more undemanding than most; Previn, at this point, probably could roll out of bed and record an album’s worth of release-ready piano instrumentals before his morning coffee. But I wonder if it was the latter stress that explains this album’s unremitting, unsettled melancholy. The song list is all wistful standards, with nary an up-tempo showpiece to be found. Previn’s usual tricks are all here—the polytonalities, the sideways modulations, the transposition of upper harmonics into the meat of the voice-leading. (The ad aspera per astra arpeggios hung onto “Everything Happens to Me,” for instance, can be traced to the introduction to “I Can’t Get Started” on Previn’s 1958 Vernon Duke album, and from there back to Previn’s bottle-rocket break on that 1955 “Slow Boat to China” recording.) But now the whole apparatus seems to be in service of bringing out every bit of ache the material will surrender.

This is barely jazz, but it’s not really easy-listening, either, and if it’s mood music, the mood is pretty rueful. It’s a weirdly appropriate farewell to this phase of his career; you can almost hear Previn look around an empty room, close the piano lid, and turn out the lights.

← Previous: Interlude: On Authenticity | Next: Interlude: On Improvisation →