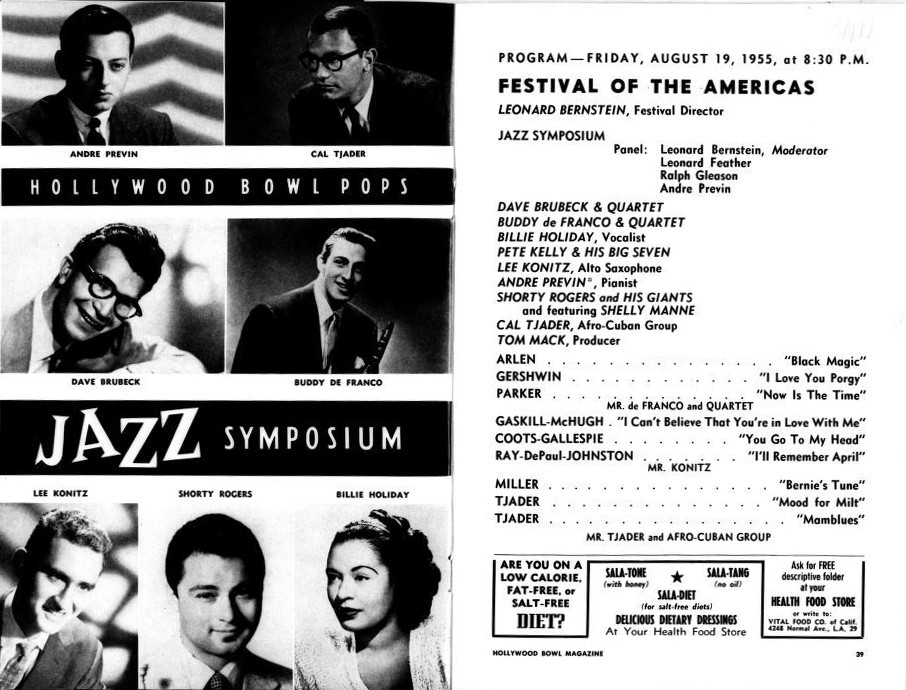

In August of 1955, the Hollywood Bowl presented an ambitious and wide-ranging “Festival of the Americas,” directed by Leonard Bernstein. Bernstein conducted the Los Angeles Philharmonic in works by himself, William Schuman, Lukas Foss, and Aaron Copland (the Lincoln Portrait, narrated by Gregory Peck). Martha Graham and her company danced three modern American ballets. Carlos Chavez guest-conducted a program of works by Latin American composers. The fourth concert was jazz: the likes of Dave Brubeck and Shorty Rogers shared the bill with Lee Konitz and Billie Holiday.

Though he wasn’t listed as such in the program, Previn apparently was a main organizer of the concert. (At least one source listed him as the concert’s music director.) That would explain Previn’s presence on a panel alongside Leonard Feather and Feather’s fellow critic Ralph Gleason, with Bernstein moderating the discussion. It would also explain why the players on the program skewed so strongly toward the West Coast studio community that Previn knew best. (It might also explain why Previn himself had space on the concert for three solo numbers.) But it’s still notable that Previn would be both the quasi-impresario and players’ spokesperson, as it were, for this incursion of jazz into a festival of predominantly high-minded modern classical repertoire.

Though his recorded catalog on the 1940s and 1950s doesn’t much show it, Previn had always kept a hand in classical music. He had played at the Hollywood Bowl as early as 1946, when he was a contestant in the KFI-Hollywood Bowl young performers competition. (He placed third, winning a $100 scholarship.) He returned several times over the next few years, both as a conductor and a soloist. In 1949, he made his first appearance at Evenings on the Roof, the new-music-heavy chamber series that eventually evolved into the Monday Evening Concerts; Previn would return to the series many times, in music from Beethoven to Hindemith. He played twelve-tone music by Rolf Liebermann; he played Stravinsky’s Serenade in A with the composer looming in the front row. (“You have wonderful fingers,” Stravinsky told Previn, Delphically.) One program opened with Previn and Lukas Foss in a Mozart four-hand sonata, a performance, Previn remembered, prepared on two days’ notice after series director Lawrence Morton told each player, neither of whom were familiar with the score, that the other had played it many times. (Both Tynan’s 1957 profile of Previn in Downbeat and a 1959 profile in Time say that Foss and Previn recorded a four-hand Mozart album for Decca, but, despite the apparent existence of liner notes by Morton, as well as a discography entry by Michael Gray, I cannot find any hint that such a recording was ever released. Foss did record some Mozart duets with Walter Hendl.)

Before he went into the army, Previn recorded The Story of a Piano (RCA Victor, 1952), a children’s album with narrator Hans Conried telling the tale of a piano who makes its way from the factory to a music school to a nightclub and beyond, always dreaming of its Carnegie Hall debut; the handful of chestnuts sprinkled in along the way—Schumann’s “Traümerei,” Chopin’s A-minor Valse—represent his classical recording debut. More serious was a 1958 recording of Ernest Chausson’s op. 30 Piano Quartet produced by Contemporary’s Lester Koenig for his brief-lived Society for Forgotten Music imprint. And, for Contemporary, Previn teamed up with violinist Nathan Rubin for a recording of the “Capriccio” by jazz clarinetist/avant-garde composer William O. Smith.

But Previn’s real arrival as a classical artist on record came in 1959. And, tellingly, it was not in European or avant-garde repertoire but, rather, in music of the original jazz-to-classical crossover artist: George Gershwin. Previn’s recording of the Rhapsody in Blue and the Concerto in F, with conductor Andre Kostelanetz and his orchestra, was also his debut on the Columbia label. Previn’s rendition is very much that of a jazz player. Earl Wild or Jesús Maria Sanroma, say, had treated Gershwin’s scores—brilliantly—as a kind of jazz-tinged Rachmaninoff, but Previn’s rendition is more brittle and brash. (Over the years, the pendulum of Gershwin interpretation would eventually swing back toward Previn’s approach.)

After 1960, Previn would, for a few years, move virtually all of his recording activity to Columbia and, later, RCA Victor as well. The change was in keeping with both his classical and jazz ambitions—Columbia’s CBS Masterworks and RCA were the leading American classical labels, but Columbia also boasted an enviable jazz roster: Brubeck, Ellington, Miles. Both labels were also much larger concerns than Contemporary, with production and marketing capacity across all genres that Contemporary could never match.

Which brings us to Previn’s shift into what would later be characterized as easy-listening. To be sure, Previn’s orchestral-pop and/or piano-with-strings records would always be more jazz-inflected than many others on the racks, but it’s the sort of music that a label like Contemporary would largely eschew. Columbia and RCA Victor were well set-up to fund, promote, and sell easy-listening albums; Previn was well-trained to record and conduct them. A sympathetic critic could characterize Secret Songs for Young Lovers and its successors as descendants of, say, Charlie Parker with Strings and the like, but none of the critics were that sympathetic; by the time Previn’s efforts, even the most overtly jazzy, hit the market, they would be filed with Jackie Gleason’s mood-music records, or Percy Faith, or Kostelanetz’s more syrupy releases, and so on. Previn, as far as I can tell, considered it a job, one he could do easily, one he could do well, one that could make him and his label money, giving him the wherewithal to pursue his classical ambitions.

Jazz, too, became a kind of leverage, especially once Previn added classical conducting to his portfolio. Red Mitchell recalled barnstorming tours in which the Previn-Mitchell-Capp trio would perform half a concert, after which Previn would conduct the local orchestra, building up his status and experience as a guest conductor. (Previn’s initial forays as a classical conductor were an odd combination of exceptional privilege—Ronald Wilford of Columbia Artists Management took him on as a client immediately—and several years of on-the-road dues-paying.)

Throughout the 1960s, one feels Previn’s jazz and jazz-adjacent work and his classical work slowly change places, the moonlighting becoming the day job and vice versa. How much of Previn’s trajectory was calculated and how much of it was improvised is an open question. But, if Previn’s easy-listening albums were part of a career bargain, one could say that Previn got the better end of the deal: within a decade of his Gershwin album with Kostelanetz, Previn was (temporarily) done with jazz and (permanently) done with mood music, free to pursue his calling as a conductor. All it cost him was his reputation among the jazz cognoscenti.