Hits and Hi-Fi.

Leonard Feather’s West Coast Stars and East Coast Stars: West Coast vs. East Coast: A Battle of Jazz (MGM, 1956) (recorded January 1956)

A very Leonard Feather-ish project from the critic and composer: put together a group of Californians and a group of New Yorkers and have them each record the same five tunes. The result shows how quickly the “West Coast” label was becoming something of a mannerism—or even an epithet. The arrangements for the West Coast group (by Pete Rugolo and, in a couple of instances, Feather himself) lean heavily toward the intricate and the fussy; Rugolo’s rendition of “Sidewalks of New York” (here retitled “East Coast, West Coast”) is a real misfire, with waltz-time fragments of the tune interrupting any possibility of extended swing. On the whole, the New York contingent (playing arrangements by Feather and Dick Hyman) comes off better, regarding the assignment with the casual bemusement it deserves.

The West Coasters have their moments, though: Buddy Collette, on reeds and flute, is smooth as silk, and trumpeter Don Fagerquist takes some truly excellent solos. Previn is never less than professional, even when tasked with negotiating the vibories, a keyboard-mounted-vibraphone contraption that Feather tried to get into the mainstream for a while. (Even after a couple choruses, Previn is still trying to adjust his rhythm to the instrument’s noticeable lag between keypress and sound.) But you can sense that Previn is playing it safe, retreating a bit into skilled but conservative tastefulness—indicative, perhaps, of how important having familiar collaborators was becoming to Previn. (This was one of the only times he recorded with drummer Stan Levey, for instance.) Only on the final number, “Lover Come Back to Me”—a performance featuring both groups, spliced together, with Hyman on organ and Previn on piano—does Previn go in for something a little more eccentric and loose.

The presence of Collette is worth noting. He was one of a handful of Los Angeles musicians who straddled the complementary milieus of Central Avenue jazz and the film and television studios. He started in the clubs, playing with the likes of Eric Dolphy and Charles Mingus, before bandleader Jerry Fielding hired him to be part of the on-air band for You Bet Your Life; when the show moved to television, Collette—at the time, the band’s only black member—broke a broadcasting color line. (Collette was also instrumental in the integration of the musicians’ union in Los Angeles, steering the whites-only and blacks-only locals into an amalgamation.) Previn and Colette had been fellow sidemen on Lyle “Spud” Murphy’s twelve-tone recording session, and occasionally would work together again on record and for film. But, again, Previn’s connection to Collette was not through the Central Avenue jazz community, but through the studios. For the most part, that would remain the pattern for Previn’s jazz collaborations until he left the movie business.

Shelly Manne & His Friends (Contemporary, 1956) (recorded February 1956)

Shelly Manne played with everybody. By 1956, he had already released several albums as the leader of Shelly Manne & His Men, the sort of revolving-door collective that was common to the West Coast scene. (Shorty Rogers had his Giants; Manne had his Men.) As a sideman, he seemed to never stop working; to peruse his discography is to wonder where he found the time to eat or sleep. But it was the drummer’s collaboration with Previn—officially inaugurated with this album—that would provide Manne (and Previn) with the biggest hit. That’s still to come. This, their first effort, is a decidedly miscellaneous collection, alternating popular-song standards with more specifically jazz-oriented compositions.

Filling out the trio was bassist Leroy Vinnegar, a more recent arrival to Los Angeles. After coming up through the Indianapolis and Chicago scenes, Vinnegar had established himself on the West Coast when, in 1954, he substituted for Red Callender behind Art Tatum for a series of San Francisco shows. Drummer William Douglass, who played for Tatum in the pianist’s last years, remembered it this way:

Nobody had heard of Leroy Vinnegar at all until Leroy Vinnegar worked with us. Then everybody wanted Leroy Vinnegar…. [W]hen we got back here, that’s when Shelly Manne and André Previn grabbed a hold of him…. I mean, Tatum was a good enough reference. They see you in the club, you’re playing with Art Tatum, and then all of a sudden you’re available over here. Who do you think you’re going to call?

Douglass claimed that Vinnegar was only comfortable in certain keys, and only kept up with Tatum because Tatum had compiled a book of written-out bass lines for his sidemen. Actually, Vinnegar played by ear, and, as he admitted, only learned to read music after arriving in Los Angeles. His acceptance into the Los Angeles jazz milieu was swift, his spare, in-the-pocket style soon gracing numerous recording sessions. Vinnegar was definitely a player who liked to do more with less. He picked up the nickname “The Walker” for his prevalent quarter-note and half-note bass lines, a penchant on ample display with Previn and Manne. Manne’s headline status and Vinnegar’s presence notwithstanding, though, this is very much Previn’s show; he stretches out on every number. What it reveals is Previn’s increasing reliance on and indulgence of his quicksilver ability to shift gears and styles at will.

Most interesting in that regard is the trio’s essaying of Oscar Pettiford’s “Collard Greens and Black-Eyed Peas” (aka “Blues in the Closet”), made famous by Bud Powell. It’s an early example of Previn playing the blues at length. The way Previn plays the blues throughout his career provides a revealing vantage on his jazz playing. To his detractors, it was his greatest liability. Previn didn’t come to understand the blues from within, but assimilated it from without. His blues would never have the authority of Ellington, or Parker, or Powell. But Previn played the blues a lot; almost every one of his jazz albums features some form of it. I think what drew Previn back to the blues was its capacity for making connections between players, its status as a kind of common knowledge across jazz generations and styles and factions. And, as we will see, it was that sort of in-performance camaraderie that was, to Previn, the real merit of jazz—of all music-making, really.

On “Collard Greens,” Previn doesn’t try to match Powell; the tempo is notably slower, and the tune is barely present. Instead, Previn switches between fast, double-time, single-note bop lines; chunkier hard-bop blues licks and accents; block-chord passages reminiscent of big-band horn sections; and far-out modernist excursions. Yet no idea sticks around for long—every phrase jumps to a different channel.

From moment to moment, it’s diverting; as a whole, it makes curiously little impression, never settling into any sort of rhetorical groove. Previn likes to deconstruct, but the blues resists deconstruction. Still, it’s a hint of how Previn will, in the future, mediate between the blues and his own eclectic musical personality. Especially toward the end of his career, Previn’s blues-based originals will be the repository of some of his most playfully tricky and even goofy jazz ideas.

Standards, though, would always be one of Previn’s greatest strengths. With a musical background not dissimilar to many of the great American pop songwriters, Previn could take apart a standard and put it back together with ease. This album’s pleasantly surreal take on “I Cover the Waterfront,” Previn taking in the landscape from a variety of unexpected vantages, is a particular highlight.

The track is the album’s best ensemble performance as well. On some tracks, you can hear the players still feeling each other out, but here, everything clicks. Manne uses the drums’ melodic potential for some lovely counterpoint, Vinnegar finds some deep-seated synchronization, and everyone seems to be thinking in concert.

Frank Sinatra Conducts Tone Poems of Color (Capitol, 1956) (recorded February 1956)

Caveat: this album falls outside even the loose definition of “jazz” governing inclusion in this survey, but it’s too cool (and weird) to leave out. Sinatra, a “frustrated conductor” by his own estimation, commissioned a bunch of Hollywood composers—Victor Young, Jeff Alexander, Nelson Riddle, Elmer Bernstein, Previn—as well as his friend Alec Wilder to write orchestral works to correspond with color-themed poems by Norman Sickel (who had written for Sinatra’s radio shows). The recording sessions were the first in the studios in the newly-constructed Capitol Building at Hollywood and Vine. Sinatra was always a better conductor than one would have thought—though he couldn’t read a score, he knew how to work with musicians—but this record was a trial. The studio space was untested, the sound in the room was dead, and the musicians were frustrated. (After one playback, Sinatra turned to principal cellist Eleanor Slatkin and asked what she thought. “I think it sounds like shit,” Slatkin replied.)

Still, it’s a fascinating project: a bunch of the industry’s best orchestrators turned loose in the candy store. Previn gets the last word on the album; “Red, the Violent” very much shows his growing interest in 20th-century British music, with echoes of Holst, Vaughan Williams, and Britten swirled into flamboyant Technicolor.

I’m reasonably sure that this photo is from these sessions, showing Sinatra in action while Previn keeps an eye on the receipts.

Given their rapport on Songs by Sinatra (musical and otherwise), it’s a little strange Previn and Sinatra did so little other work together. (Perhaps the memories of The Kissing Bandit were just too painful.) Nowadays, type their names into a search engine, and you’ll have to scroll past pages of references to the fact that they both married Mia Farrow before anything like the Tone Poems album appears.

Dave Pell Octet: Love Story (Atlantic, 1956) (recorded spring 1956?)

Reed player Dave Pell’s octet was a constantly shifting ensemble à la Rogers’ Giants or Manne’s Men; this was Previn’s only date with the group. He doesn’t even play the entire album; Claude Williamson takes over on piano for four numbers. And neither has much to do: the arrangements, by a clutch of Los Angeles pros—Marty Paich, Jack Montrose, and others—keep everybody on fairly tight leashes. Apart from a half-chorus in Johnny Mandel’s up-tempo arrangement of “I’ve Found a New Baby,” Previn does little more than comp.

Previn does, however, contribute an arrangement of “Bewitched” that dissects the tune with notably more flint than the rest of the album’s almost easy-listening smoothness.

(Note: Some sources have Previn playing on three tracks of another Pell album, The Big Small Bands (Capitol, 1960), but he’s absent from the original sleeve’s otherwise diligent list of personnel.)

Hollywood at Midnight (Decca, 1957) (recorded March 1956)

This was one of a series of albums of mood music that Decca released all at once: Carmen Cavallero did Rome at Midnight, Skitch Henderson did London at Midnight, Ellis Larkin did Manhattan at Midnight, and so forth. Previn’s entry finds a very accomplished band—he’s joined by Manne, Al Fredrickson on guitar, and Carson Smith (Putter’s elder brother) on bass—lounging around in very moderate tempi, with the occasional double-time solo to remind the listener of their jazz bona fides. The result falls in between what will soon be a genre boundary, though not in a bad way—it’s pretty smoothed-out for jazz, but the finish is exceptional, and pretty advanced for mood music, but still able to effectively set the mood. (The group’s take on David Raskin’s “Laura” theme is particularly nice.) It won’t be the last time Previn straddles easy-listening and jazz in a way that obscures which is the figure and which is the ground.

Barney Kessel: Music to Listen to Barney Kessel By (Contemporary, 1957) (recorded August 1956)

In similar vein to Pell’s octet efforts were guitarist Barney Kessel’s recordings for Contemporary. Previn did a single, August 1956 session for this album, appearing on only four tracks. (Two more sessions, in October and December, featured Jimmy Rowles and Claude Williamson.) Much like Dave Pell’s Love Story, a mid-sized group delivers tight but easygoing arrangements of standards with light modernistic touches. Previn (who, recall, played with Kessel as a sixteen-year-old Jubilee guest) stays in the background on a spiky “Fascinating Rhythm,” comps aggressively in a Latin-flavored “I Love You,” and contributes short, slinky, quicksilver solos to “Gone with the Wind” and “Makin’ Whoopee.” Maybe too short—Previn’s solo on the latter practically stumbles to a close, as if he was expecting it to go on for another chorus or two.

Previn also wrote the complimentary, largely descriptive liner notes, and his placid, precise tone is an amusing contrast with the Leonard Feather-Nat Hentoff school of notes. To wit:

GONE WITH THE WIND is third, a relaxed and relaxing exercise in the Shearing sound. It is unpretentious, well-scored, and pleasant in the extreme.

Coming from anyone else, that would be damning with faint praise. Hearing it in Previn’s voice, it sounds like the highest regard.

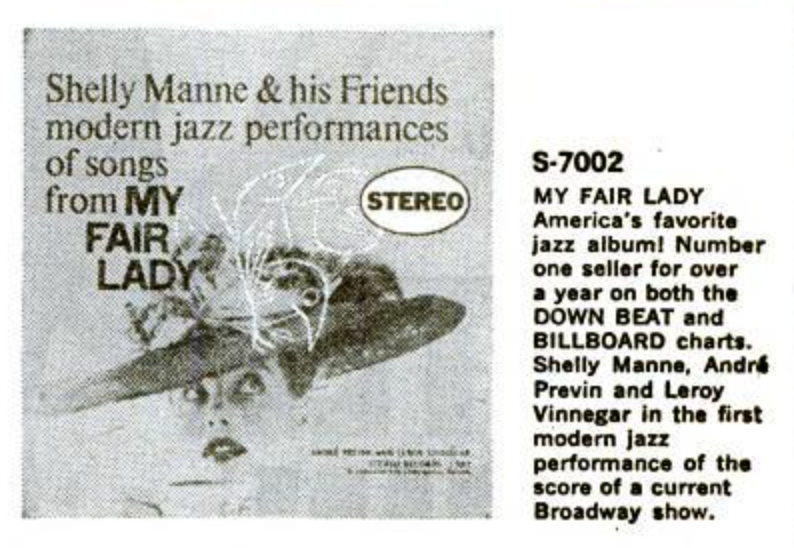

Shelly Manne & His Friends: Modern Jazz Performances of Songs from My Fair Lady (Contemporary, 1956) (recorded August 1956)

It’s worth mentioning that, at the time of this recording, Previn was still only 27 years old. He had established himself enough for Feather to recruit him as a “West Coast All-Star,” but this record would bump his celebrity to another level. The second Manne-Previn-Vinnegar “Friends” effort was originally intended to be a collection of unrelated show tunes, but after trying out a couple of songs from that year’s Broadway hit, Lerner and Loewe’s My Fair Lady, either Manne and Previn, and Vinnegar (who, after all, had been part of Bethlehem Records’ complete jazz Porgy and Bess earlier in the year) or producer Lester Koenig came up with the idea of filling the entire album with the show’s songs. As Manne remembered it to Robert Gordon:

[W]e found that there was so much material in there that we could use, and change, and construct to the way that would suit us best, we said, “Let’s go ahead and use this other material.” There was no thought of, “Hey, we’re making a hit record,” it was just the thought of making another good record, but not using the same old standard material but using new material from a new show. And as it worked out, of course, it was a smash! Of course Andre, with his knowledge of harmony and composition, was fantastic. He’d play something and he’d say, “Oh, let’s do this at this tempo,” and we’d play it and I’d say, “That’s great!” And he’d play something else at a fast tempo, and I’d say, “Why don’t we try that as a ballad?” There was a total thing going back and forth.

By all accounts a fairly thrown-together affair (it was arranged and recorded in a single, all-night session), the result was an enormous hit, which caught the performers by surprise. Previn would later tell of his apprehension that Lerner and Loewe would find the record offensive; instead, they bought copies for the show’s entire cast and crew. (It’s occasionally cited as the first jazz album to sell a million copies, which might be an exaggeration—I can’t find any solid evidence of that figure—but Billboard, in 1962, put the sales at nearly 500,000, which is still plenty.)

So what about the album itself? It’s solid and polished, witty and occasionally inspired, but also (see below) planting the seeds of a distinction between jazz-as-an-improvisatory-and-exploratory-practice and jazz-as-a-stylistic-marker that Previn will sail between—and, critically, be buffeted against—for the next few years. There’s a lot of groove and energy, as well as instances of note-spinning. It’s invariably crisp and engaging—the players are all too good for it to be otherwise. And here and there the group finds a higher gear. The head arrangement of “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly” is almost too cute, but it turns into a vigorous, satisfying workout.

And Previn’s playing on “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face” is unimpeachably elegant, with a restrained andabsolutely gorgeous solo.

The Previn-Vinnegar-Manne trio was a short-lived outfit, but not a small pleasure of this album is hearing how, again and again, they settle into an easy professional rapport.

While not quite the first example, the record jump-started the fad of jazz albums devoted to a single Broadway show, and became by far the Contemporary label’s biggest-selling release. And, with success came disdain. In an essay in the June 1959 issue of HiFi Review, critic Charles M. Weisenberg credited/blamed My Fair Lady for inventing what he called “light jazz”—“quasi-jazz,” in Weisenberg’s estimation, as contrasted with “true jazz” or “real jazz” or “quality jazz”. His argument proceeds from this postulate:

The creative jazz musician owes small allegiance to the composer of any number because when his tune is subjected to expression, the rhythms, moods, and even original melodic lines are often drastically reconstructed. This is part of the way a jazzman thinks, and thereby produces a new art work out of another person’s music. It is just this “re-composing” that the jazzman is not free to do when performing from a Broadway score.

Weisenberg’s insistence that true jazz cannot be “based on music from Broadway instead of the blues” is slightly baffling (and ahistorical) but allows him to keep Previn et al. safely outside the city walls.

Previn does remarkable things on his recording but they cannot be judged in jazz terms, even though that was his intent. The music here always remains familiar as My Fair Lady, only with a touch of something different…. The jazz flavor is unmistakable enough, but hard core enthusiasts find the treatment quite superficial. Those who have thought that jazz was something they could never tolerate are the ones who may find this music most palatable.

This sort of judgement is going to dog Previn more and more, particularly as he adds easy-listening pop to his portfolio. It’s a perfect storm: the community of jazz critics framing “authentic” jazz in a way that will run headlong into Previn’s stylistically-indiscriminate fluency.

Pete Rugolo and His Orchestra: An Adventure in Sound: Brass in Hi-Fi (Mercury, 1956) (Previn’s tracks recorded October 1956)

Pete Rugolo and His Orchestra: An Adventure in Sound: Reeds in Hi-Fi (Mercury, 1958) (Previn’s tracks recordedNovember 1956)

Rugolo (who we’ve already heard via Feather’s East Coast/West Coast exhibition match) had the quintessential West Coast jazz résumé: studies with Darius Milhaud at Mills College, a stint in the U.S. Army band alongside Paul Desmond, steady work as an arranger and producer with Miles Davis (he produced the Birth of the Cool sessions), Nat “King” Cole, and, especially, Stan Kenton. After Kenton dissolved his orchestra, Rugolo shifted into film and, eventually, television work. At the time of the sessions for these albums—part of a string of Rugolo-directed hi-fi spectaculars—he was still four years away from claiming one of the all-time great film credits (from the 1960 MGM college-girls-on-holiday picture Where the Boys Are):

Rugolo’s trajectory throughout the 50s was away from jazz as an improvised practice and toward jazz as a modernistic, fully-arranged style. “Igor Beaver,” from the Reeds in Hi-Fi album, is the most modernistic and fully-arranged, refracting Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms through a prism of sharp Kenton-esque riffs. But, here and elsewhere, the opportunities for individual players to stretch out on solos are brief and strictly rationed.

Recording sessions for these two albums were scattered throughout 1956; Previn’s two days of work made him one of three pianists on the finished product, alternating tracks with Claude Williamson (see above) and Russ Freeman (see below). Not surprisingly, he doesn’t do much beyond hitting accents and comping. On the Brass album, Previn has concise solos on the old Baer-Wolfe “My Mother’s Eyes,” George Wallington’s “God Child,” and the Rugolo original “Brass at Work”—throughout, Previn’s reflexive elegance provides brief respites from the album’s more-is-more sonic profile. There’s another short solo on Gerry Mulligan’s “Walking Shoes” on the Reeds album (bearing more than a little resemblance to Previn’s corresponding spotlight on “Brass at Work”). But it’s “Our Waltz” that is the most curious. Maybe it’s only a coincidence that much of Previn’s job on the split-personality arrangement is, essentially, to epitomize his career, keeping one foot in the club and one in the studio soundstage. And maybe it’s another coincidence that the song’s composer, David Rose, and Previn will soon team up again.

George Byron: Premiere Performance! George Byron Sings New & Rediscovered Jerome Kern Songs (Atlantic, 1959) (recorded November 1956, April 1957)

George Byron’s career had included a few film appearances, a stint as emcee for the Ice Capades, and periodic cabaret nightclub appearances on the West Coast. He was close with Jerome Kern during the composer’s life, and, in 1951, married Kern’s widow Eva. The three premieres on this album were sketches that Eva Kern unearthed, with new lyrics by Dorothy Fields. That novelty—and his reverence for Kern’s songwriting—no doubt attracted Previn’s attention, and he supplied the lush arrangements and the piano playing. But the result struggles to generate sparks. Byron’s is a conscientious, pleasant, benign voice, but never anything more, and it’s left to Previn to create what texture there is: some jazz solos on “You Couldn’t Be Cuter,” a deft piano-only accompaniment on the Kern-Hammerstein obscurity “The Folks Who Live on the Hill,” and, for Kern’s 1905 “How’d You Like to Spoon with Me?,” some full-on old-timey hijinks, including a few bars of exceptionally out-of-tune honky-tonk.

Buddy Bregman: Swinging Kicks (Verve, 1957) (recorded December 1956)

The IMDB description of the 1956 film The Wild Party is one of those sentences that just keeps getting better: A night of terror in a sleazy nightspot, when an over-the-hill football star holds a thrill-seeking couple captive.

The score to The Wild Party was composed by Buddy Bregman, an arranger and conductor who had become Verve’s head of A&R at the age of 25. He did the arrangements for the first two of Ella Fitzgerald’s songbooks—devoted to Cole Porter and Rodgers and Hart—which show what he did best: punchy, riff-based, harmonically-straightforward big-band swing. That’s on ample display on this album, for which Bregman refashioned his Wild Party efforts into a kind of suite. It still has the episodic feel of a film score, with many of the tracks not even two minutes long. It’s like a packet of postcards, souvenirs of a trip through Hollywood’s version of a jazz-tinged underworld: brash and swaggering, but also incongruously luxe and polished.

The band features all manner of West Coast jazz royalty—Maynard Ferguson, Conte Candioli, Ben Webster, Jimmy Giuffre. Piano duties are divided between Previn and Paul Smith, and it’s not always clear who’s playing what. But it’s definitely Previn on the finale, “Kicks Is in Love,” an aristocratic duet with Webster that shows off Previn’s skill as an accompanist.